Unlock Editor’s Digest for free

FT editor Roula Khalaf selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In post-war Paris, signs often appeared above kitchens stating that the owner ate his own meals, which, given the food rationing of the time, testified to the chef’s confidence in his dishes.

This phrase springs to mind in the debate surrounding proposed reforms to the UK’s listing rules. Corporate boards and pension funds are making a coordinated, last-ditch effort to block changes that would allow dual-class share structures (DCSS) without a mandatory sunset clause and remove the requirement for shareholder approval for significant related-party transactions.

In their letters to the UK financial regulator, the International Corporate Governance Network and a coalition of UK pension funds pull no punches, arguing that the rule changes could discourage investment in UK-listed shares, drive up the cost of capital for UK companies and undermine London’s status as a financial centre – a triple blow for beleaguered Britain.

The pension funds state that the proposals (emphasis by Alphaville):

. . . Will make the United Kingdom less attractive as a destination for capitalwhich exacerbates the current problems by making UK listed companies less attractive for the kind of high-quality, long-term investors our companies are looking for before and after the IPO. This in turn could Increase in the cost of capital for UK listed companies because investors demand a higher return for the increased risk.

Similarly, the ICGN letter – co-signed by shareholder and management groups from Portugal, Italy, Canada and Australia – argues that the UK’s high standards set it apart from other countries and attract investors from around the world. Relaxing these standards could deter the foreign investors so important to the London market (again, our emphasis):

The UK’s reputation as a provider of high-quality listing and governance standards and the resulting trust of foreign investors are both a competitive advantage and a positive differentiator for the UK market in a global context. According to the … Office for National Statistics, the share of shares in UK companies listed on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) held by foreign investors rose to a record 57.7% of the value of the UK stock market in 2022 … [B]The listing in the British premium segment is a strong signal that the company adopts the highest governance standards and is well positioned for long-term success. . .[M]Market integrity is something that must be preserved and not watered down.

The wording contains an implicit but unambiguous threat to leave the United Kingdom.

The merits of the reforms are balanced and have been hotly debated. The ICGN cites studies that suggest the benefits of dual-class share structures disappear after seven years, although the letter does not make any direct claims of downside. In fact, it is not difficult to find counterexamples, and indeed the area is an academic minefield, with various studies struggling to find any link between corporate governance and company performance. Whether long-term DCSS empowers visionaries or cements subpar management depends on myriad factors that fund managers have been able to judge for themselves elsewhere.

Whatever the pros and cons, two points overshadow the conscientious objectors’ arguments. First, their investment choices belie their statements. The majority of their share portfolio is invested in companies and markets whose corporate governance practices they denounce. Second, their assumption that high standards attract investment is unfounded and probably incorrect in the UK context.

First, the institutions represented by ICGN appear to have no qualms about investing in markets with less stringent standards, such as the US and several European countries. Members include some of the largest investors in dual-class share structures and in markets that do not require shareholder approval for significant and related transactions. Presumably, corporate governance in these other areas is good enough to make their listed shares investable.

So there is a clear disconnect between the advocacy of governance groups and the actions of investment teams. The ICGN letter does not address this inconsistency, nor does it explain why the UK should be uniquely held to stricter standards than the other markets in which its members like to invest.

UK pension funds have now largely withdrawn from the domestic stock market and now hold just four percent of their total investments. Pension funds have withdrawn a large proportion of their assets from listed equities and, to the extent that they are still invested, hardly hold any UK equities. Here is an extract from editorial author Railpen’s factsheet on his Global Equity Fund:

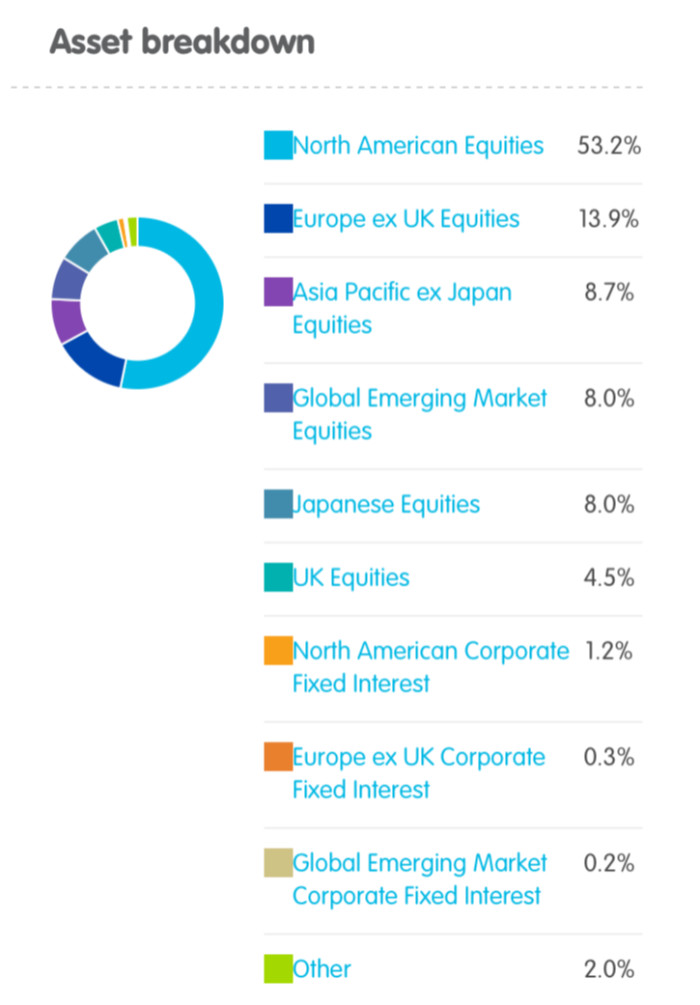

Or the disclosed allocation of the “Global Investments (up to 100 percent shares) Fund” of the co-signatory People’s Partnership:

And the top 10 holdings are all American and include companies with multiple share classes:

A similar story is told by another signatory, Brunel Pension Partnership. The top 20 holdings in each of its four non-regional active equity funds contain just one UK-listed stock; the 80 names are predominantly American and include dual-class share structures and even some Chinese companies.

This is not a criticism of their investment decisions. On the contrary: multi-class public companies like Alphabet and Meta have been phenomenal stocks! But the critics’ investment decisions make their implicit threat to pull their money out of the London market ring hollow. British pension funds, as HSBC analysts recently pointed out, “have nothing left to sell.”

Since the pension funds have so little vested interest in the (listed British) business, one can hardly speak of “self-serving interests”. Rather, they are more of “uninvested interests”.

Nor is it possible to believe the groups’ claim that London’s strict standards attract investment and thus lead to a lower cost of capital. The commentators do not cite any studies to support this claim, nor do they attempt to reconcile it with the cheap valuation and consistent underperformance of UK equities.

Although the ICGN and UK pension funds warn that lowering governance standards could deter investment, their own investment practices suggest a more nuanced reality. It is probably more accurate to say that once governance reaches a minimum acceptable level, other factors take precedence. Overly stringent standards may not attract investment and may even be counterproductive by distracting management or discouraging companies from listing.

The proposed stock market reforms are the first, small steps in the campaign to rehabilitate London as a stock market after a turbulent period marked by delistings, reduced liquidity and an IPO lull. Much more needs to be done, particularly in the areas of pensions, insurance and tax, and these efforts will be closely scrutinised, debated and contested by various stakeholders. It would not bode well for the City’s recovery if the UK could not even change its listing rules to bring them in line with those of the rest of the world.

There is a fine line between principle and complacency, and Britain has seen little benefit from the penitential garb of its stricter standards.