Our planet was formed around 4.5 billion years ago. To understand this incredibly long history, we need to study rocks and the minerals they are made of.

Australia’s oldest rocks, among the oldest in the world, were found in the Murchison district of Western Australia, 700 kilometers north of Perth. Their age has been dated to almost 4 billion years.

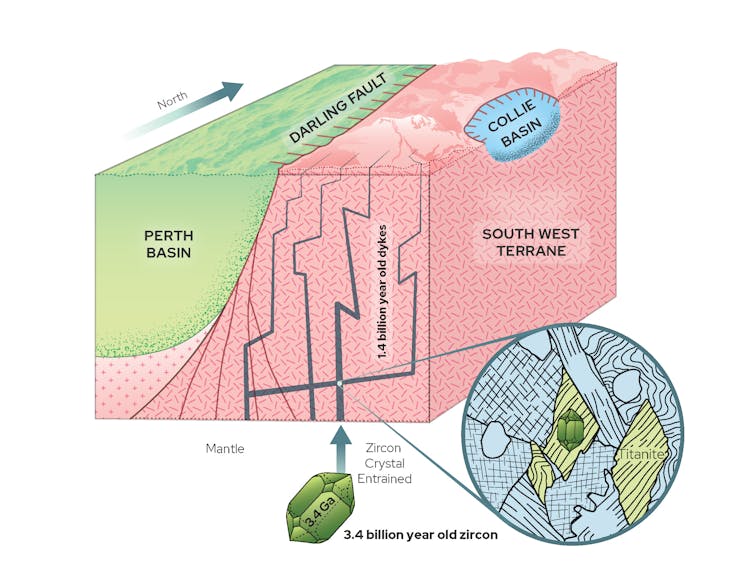

In a new study, we have found evidence of rocks of similar age near Collie, south of Perth, suggesting that Western Australia’s ancient rocks cover a far larger area than we thought and are buried deep in the Earth’s crust.

The old continental crust

The ancient crust of Australia is crucial to understanding the early Earth because it tells us about the formation and evolution of the continental crust.

The continental crust forms the basis of the land masses on which people live, supports ecosystems and provides important resources for civilization. Without it, there would be no fresh water. It is rich in mineral resources such as gold and iron and is therefore of economic importance.

However, studying ancient continental crust is not easy. Most of it is deeply buried or has been heavily modified by the environment. There are few exposed areas where researchers can directly observe this ancient crust.

To understand the age and composition of this hidden ancient crust, scientists often resort to indirect methods, such as studying eroded minerals preserved in overlying basins or using remote sensing of sound waves, magnetism or gravity.

However, there may be another way to look deep into the crust and, with a bit of luck, even take a sample of it.

Retrieving crystals from the depths

Our planet’s crust is often cut by dark fingers of magma rich in iron and magnesium that can extend from the upper crust down to the mantle.

These structures, called dikes, can originate from a depth of at least 50 kilometers (much deeper than even the deepest borehole, which is only 12 kilometers long).

These dikes can capture tiny amounts of minerals from deep below and transport them to the surface where we can study them.

In our recent study, we found evidence of ancient buried rocks by dating zircon grains from one of these dikes.

Zircon contains trace amounts of uranium, which decays into lead over time. By accurately measuring the ratio of lead to uranium in zircon grains, we can determine how long ago the grain crystallized.

This method showed that the zircon crystals from the dike are 3.44 billion years old.

Titanite Armor

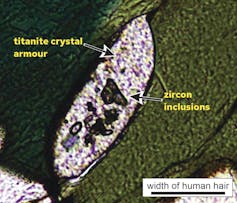

The zircons are encapsulated in another mineral called titanite, which is chemically more stable than zircon in the dike. Imagine a grain of salt trapped in a hard-boiled sugar candy falling into a cup of hot tea.

The stability of the titanite armor protected the ancient zircon crystals from changes in chemical, pressure, and temperature conditions as the dike moved up. Unprotected zircon crystals in the dike were greatly altered during the journey, wiping out their isotopic records.

However, the titanite-armored grains remained intact and provide a rare insight into the early history of the Earth.

The dyke itself, dated to be about 1.4 billion years old, provides a unique glimpse into the Earth’s ancient crust that would otherwise have remained hidden. We also found similar ancient zircon grains further north in the sands of the Swan River, which flows through Perth and drains the same region, further confirming the age and origin of these ancient materials.

The results extend the known area of ancient crust previously identified in the Narryer area of the Murchison District.

One reason it is important to understand the deep crust is because we often find metals at the boundaries between blocks of that crust. Mapping these blocks can help map zones that can be investigated for mining potential.

Remains from prehistoric times

So the next time you pick up a rock and rub some mineral grains on your hand, think about how long those grains have been around.

To get a sense of the timescale, imagine that the history of our planet lasted one year. Earth formed from swirling dust 12 months ago. Every handful of sand you pick up in Perth contains one or two grains of sand from about ten months ago. Most of Australia’s gold was formed seven months ago, and land plants arrived just a month ago.

Dinosaurs appeared two weeks ago. All of humanity has been here for the last 30 minutes. And you? Soberingly, on that scale, your life would last about half a second.![]()

Chris Kirkland, Professor of Geochronology, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.