Deshnee Naidoo has spent her career climbing the mining ladder and finds the change in attitudes towards women “phenomenal.”

But recently, the former boss of nickel and cobalt producer Vale Base Metals has noticed a disturbing backlash. When applicants from diverse backgrounds get a job, some men in the industry use the acronym DEI – diversity, equity and inclusion – in a pejorative way: “Didn’t Earn It.”

“I’m hearing more and more voices against wokeism. It’s not yet clear whether this trend will prevail,” says 48-year-old Naidoo. “We are always being led back to the way things were, instead of where they need to go.”

Naidoo’s experience shows how a transatlantic backlash against diversity initiatives – during which prominent conservatives have criticized programs such as bias training or the targeting of underrepresented groups in recruitment – threatens efforts to reduce gender inequality. In mining, one of the industries that lags furthest behind on equality, the risk of hard-won gains being undone is particularly high.

“Globally, we’re seeing this Andrew Tate effect where men are taking back power,” says Stacy Hope, executive director of advocacy group Women in Mining UK, of the self-described “misogynistic” social media influencer. “We need to take men along on this journey to make sure they become allies.”

The belief that women are promoted based on their gender rather than their skills has permeated into middle management and the boardroom, according to some female executives. Naidoo says she has been accused of being “too aggressive and pushy.” “At the executive level, despite our champions… we are just so far from where we should be,” she adds. “At the top, the industry still looks like it did yesterday.”

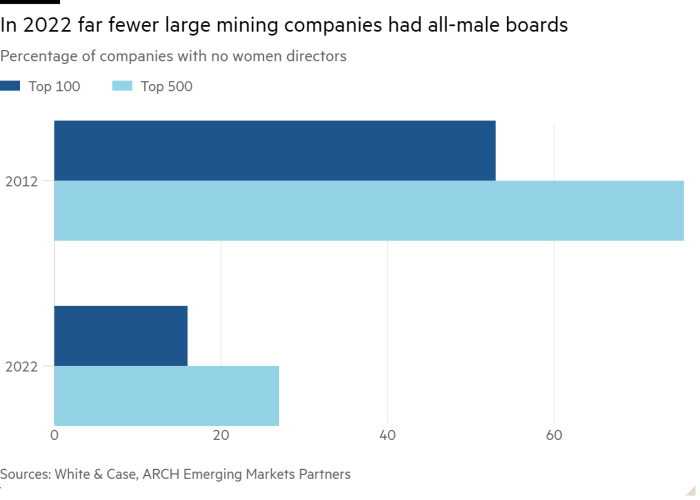

Mining has made remarkable progress in gender equality over the past decade, with the proportion of female directors at the 500 largest mining companies rising from 4.9 percent in 2012 to about 18 percent in 2022, according to law firm White & Case.

One of the most well-known female executives in mining is Australia’s richest person, Gina Rinehart, the owner of an iron ore empire who introduced pink mining trucks to raise breast cancer awareness.

But the industry is far from parity. Of the 100 largest mining companies, 16 still had no women on their boards, and one in four of the 500 largest companies had none, White & Case figures for 2022 showed. Diversity among “junior” mining companies, which explore and develop mines and make up the bulk of the industry, remains deplorable.

The battle to recruit women comes at a time when the mining sector – which is crucial for producing the raw materials needed for the international energy transition – is struggling to attract the most talented employees. Young people, executives say, are increasingly more interested in becoming data engineers than in mining.

A survey of mining industry executives by consulting firm McKinsey found that 71 percent of respondents said they are unable to meet their production targets and strategic objectives due to skills shortages. Another survey by PwC found that two-thirds of executives expect the skills shortage to have a major impact on profitability within the next decade.

A particular challenge of the extractive industry is its location: mines are often located in remote places around the world. The rural communities in which they operate sometimes have different norms than those in Western companies, leaving female workers at risk of gender-based violence or local backlash.

To meet the interests of a new generation, the industry increasingly wants to position itself as a technology and data-driven company that does not necessarily have to dig in pits or go deep underground.

“I hate it when people talk about our industry as heavy industry,” says Hilde Merete Aasheim, who last month ended her five-year term as CEO of Norsk Hydro, Europe’s largest aluminum producer. “It’s an old word, it’s not about raw muscle anymore. It’s really high-tech.”

Hope says the perception of mining as a “boys’ club” hasn’t helped it attract women. The industry needs to become “visible” to young people, including as a sector that is crucial to achieving environmental goals, such as limiting emissions to keep global warming to 1.5 degrees, she says.

“We need young people to innovate with AI and digital toolsets,” she says. “We are failing to transform the industry into one that needs young people and diverse talent to drive this change.”

Management scandals have not helped that reputation. A 2022 report on workplace culture at British-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto found that bullying and sexism were “systematic” across all sites, a finding that chief executive Jakob Stausholm called “deeply disturbing.” Rio has now partially tied executive pay to gender diversity performance and will publish the results of another investigation this year.

Elizabeth Broderick, Australia’s former gender discrimination commissioner who led the Rio report, says discriminatory incidents in mining are “not isolated workplace abuses” but “symptoms of a permissive culture”.

However, the situation across the industry is improving in some ways. The new amendment to Australia’s sex discrimination law is a “groundbreaking” step as it requires employers not only to respond to complaints but also to take preventative measures to create inclusive workplaces, Broderick says.

Norsk Hydro’s Aasheim is a woman who has benefited from the support of male bosses throughout her career, which began as a teenager in a bakery. “I never applied for a job,” she says. “But I got a lot of opportunities because I had important bosses who saw my potential and challenged me about what I could do… As leaders, we have to be active.”

But given the backlash against DEI, some say leaders need to be more proactive in embedding women’s empowerment across the workforce.

“We need to listen to men’s concerns about the changing demographics of the workforce and ensure that their fears are heard and addressed,” says Broderick. “Organizations that increase the number of women in the workforce are working [not only] to change mindsets and behaviors, but also to embed everyday respect into their systems and structures.”

Additional reporting by Nic Fildes