Seawater is pushing miles beneath Antarctica’s “Doomsday Glacier,” making it more vulnerable to melting than previously thought. This is according to a new study that used radar data from space to take an X-ray of the crucial glacier.

When the salty, relatively warm seawater hits the ice, it causes “intense melting” beneath the glacier and could mean that projections of global sea level rise are underestimated, according to the study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

West Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier – nicknamed the “Doomsday Glacier” because its collapse could cause catastrophic sea level rise – is the widest glacier in the world and is about the size of Florida. It is also Antarctica’s most vulnerable and unstable glacier, in large part because the land on which it lies is sloping, allowing seawater to eat away at the ice.

Thwaites, which already contributes 4% of global sea level rise, contains enough ice to raise sea levels by more than 2 feet. But because it also acts as a natural dam for the surrounding ice in West Antarctica, scientists have estimated that its complete collapse could ultimately cause sea levels to rise by around three meters – a catastrophe for the world’s coastal communities.

Many studies have pointed out the enormous vulnerability of Thwaites. Global warming caused by humans burning fossil fuels has left the country “hanging by its fingernails,” according to a 2022 study.

This latest research adds a new and alarming factor to predictions about his fate.

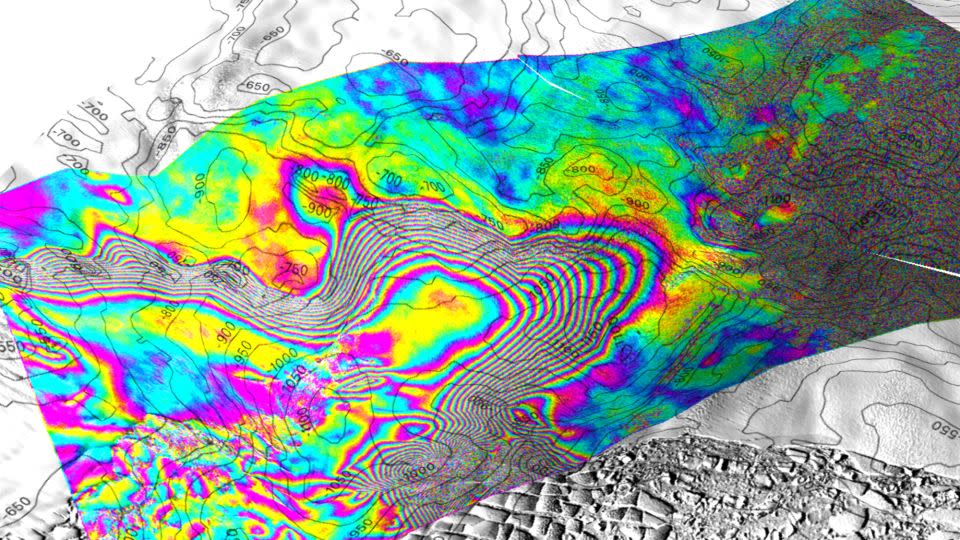

A team of glaciologists – led by scientists from the University of California, Irvine – used high-resolution satellite radar data collected between March and June last year to create an X-ray image of the glacier. This allowed them to create a picture of changes to Thwaites’ “grounding line,” the point where the glacier rises from the seafloor and becomes a floating ice shelf. Grounding lines are critical to the stability of ice surfaces and are a key weak point of the Thwaites, but have been difficult to study.

“In the past, we only had sporadic data to study this,” said Eric Rignot, a professor of Earth system science at the University of California, Irvine and co-author of the study. “In this new data set, collected daily and over several months, we have solid observations about what is going on.”

They watched as seawater pushed under the glacier for many miles and then flowed out again, following the daily rhythm of the tides. As the water flows in, it is enough to raise the surface of the glacier by centimeters, Rignot told CNN.

He suggested that the term “grounding zone” might be more appropriate than “grounding line” because, according to their research, it can move nearly 4 miles over a 12-hour tidal cycle.

The speed of seawater moving over significant distances in a short period of time increases glacier melting because as the ice melts, freshwater is washed out and replaced by warmer seawater, Rignot said.

“This process of widespread, enormous seawater intrusion will reinforce projections for sea level rise in Antarctica,” he added.

Ted Scambos, a glaciologist at the University of Colorado Boulder who was not involved in the study, called the research “fascinating and important.”

“This finding reveals a process that has not previously been accounted for in models,” he told CNN. And while these results only apply to certain areas of the glacier, he said, “This could accelerate the pace of ice loss in our forecasts.”

One uncertainty that needs to be addressed is whether the seawater rush beneath Thwaites is a new phenomenon or whether it is significant but long unknown, said James Smith, a marine geologist with the British Antarctic Survey who was not involved in the study.

“In any case, it’s clearly an important process that needs to be incorporated into ice sheet models,” he told CNN.

Noel Gourmelen, professor of Earth observation at the University of Edinburgh, said using radar data for this study was interesting. “Ironically, we are learning a lot more about this environment by going into space and using our growing satellite capabilities,” he told CNN.

There are still many uncertainties about what the study’s results mean for Thwaites’ future, said Gourmelen, who was not involved in the research. It’s also unclear how widespread this process is in Antarctica, he told CNN, “although it’s very likely this is happening elsewhere as well.”

A regime change

Antarctica, an isolated and complex continent, appears increasingly vulnerable to the climate crisis.

In a separate study also published Monday, researchers from the British Antarctic Survey examined the reasons for record-low sea ice levels around Antarctica last year.

Analyzing satellite data and using climate models, they found that this record low “would have been extremely unlikely without the influence of climate change.”

Melting sea ice does not directly affect sea level rise because it is already floating, but it does cause coastal ice sheets and glaciers to become exposed to waves and warm ocean waters, making them much more vulnerable to melting and breakup.

The researchers also used climate models to predict the potential speed of recovery after such extreme sea ice loss, finding that not all of the ice will return even after two decades.

“The impact if Antarctic sea ice remained low for over twenty years would be profound, including on local and global weather,” Louise Sime, co-author of the BAS study, said in a statement.

The findings add to evidence from recent years that the region is facing “permanent regime change,” the authors write.

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com