The Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) fascinate researchers and the public alike. They remain central to debates about the nature of the genre homo (the broad biological classification into which humans and their relatives fall). Neanderthals are also crucial to understanding the uniqueness of our species, homo sapiens.

About 600,000 years ago we shared a common ancestor with the Neanderthals. They evolved in Europe while we did so in Africa, before spreading multiple times into Eurasia. The Neanderthals died out about 40,000 years ago. We have populated the world and continue to thrive. Whether this different outcome is a result of differences in language and thinking has long been debated.

But the evidence points to key differences in the brains of our species and those of Neanderthals that made modern humans possible (H. sapiens), developing abstract and complex ideas through metaphors – the ability to compare two unrelated things. For this to happen, our species had to differ in brain architecture from Neanderthals.

Some experts interpret the skeletal and archaeological evidence as indicating profound differences. Others believe there were none. And some take the middle path.

When attempting to infer such intangibles from material remains such as bones and artifacts, it is not surprising that there is disagreement. The evidence is fragmentary and ambiguous, leaving us with a complex puzzle about how, when and why language evolved. Fortunately, recent discoveries in archaeology and other disciplines have added several new pieces to this language puzzle, allowing a usable picture of the Neanderthal mind to emerge.

Gorodenkoff / Shutterstock

New anatomical evidence suggests that Neanderthals’ vocal and auditory tracts were not significantly different from ours, suggesting that they were anatomically as capable of communicating through language as we are. The discovery of Neanderthal genes in our own species indicates multiple episodes of interbreeding, which implies effective communication and social relationships between species.

The discovery of Neanderthals’ wooden spears and the use of resins to make tools from individual components have also improved our view of their technical capabilities. Examples of symbolism include bird’s claw pendants and the likely use of feathers as body decoration, as well as geometric engravings on stone and bone.

Cave painters?

The most striking claim is that Neanderthals created art by painting cave walls in Spain with red pigment. However, some of these claims about cave art remain problematic. The evidence for Neanderthal cave art is marred by unresolved methodological problems and, in my view, is probably incorrect.

The rapidly accumulating evidence of the presence of modern humans in Europe 40,000 years ago challenges the idea that Neanderthals made these geometric patterns, or at least that they did so before the influence of symbol-using modern humans. A wooden spear, no matter how well made, is little more than a pointed stick, and throughout the Neanderthal’s existence there is no evidence of technological progress.

While the archaeological evidence remains controversial, findings from neuroscience and genetics provide a compelling argument for linguistic and cognitive differences between them H. neanderthalensis And H. sapiens.

Bokeh blur background / Shutterstock

A 3D digital reconstruction of the Neanderthal brain, created by deforming the brain of homo sapiens and the fit into a cast of a Neanderthal brain (endocast) suggests significant differences in structure. Neanderthals had a relatively large occipital lobe, meaning more brain mass was devoted to visual processing and less was available for other tasks such as language.

They also had a relatively small and differently shaped cerebellum. This subcortical structure, which is full of neurons, contributes to many tasks including language processing, speech, and language competence. The unique spherical shape of the modern human brain evolved after the first homo sapiens had appeared 300,000 years ago.

Some of the genetic mutations associated with this development are related to neuronal development and the way neurons in the brain are connected. The authors of a comprehensive study of all mutations known to be unique to homo sapiens (As of 2019) concluded that “modifications of a complex network in cognition or learning have occurred in modern human evolution.”

Iconic words

As such evidence accumulates, our understanding of language has also changed. Three developments are of particular importance. First, in 2016, it was discovered through brain scans that we store words, or rather the concepts we associate with words, in both hemispheres of the brain and in clusters or semantic groups of similar concepts in the brain. This is significant because, as we will see, the way in which these clusters of ideas connected—or not—was likely different H. sapiens and Neanderthals.

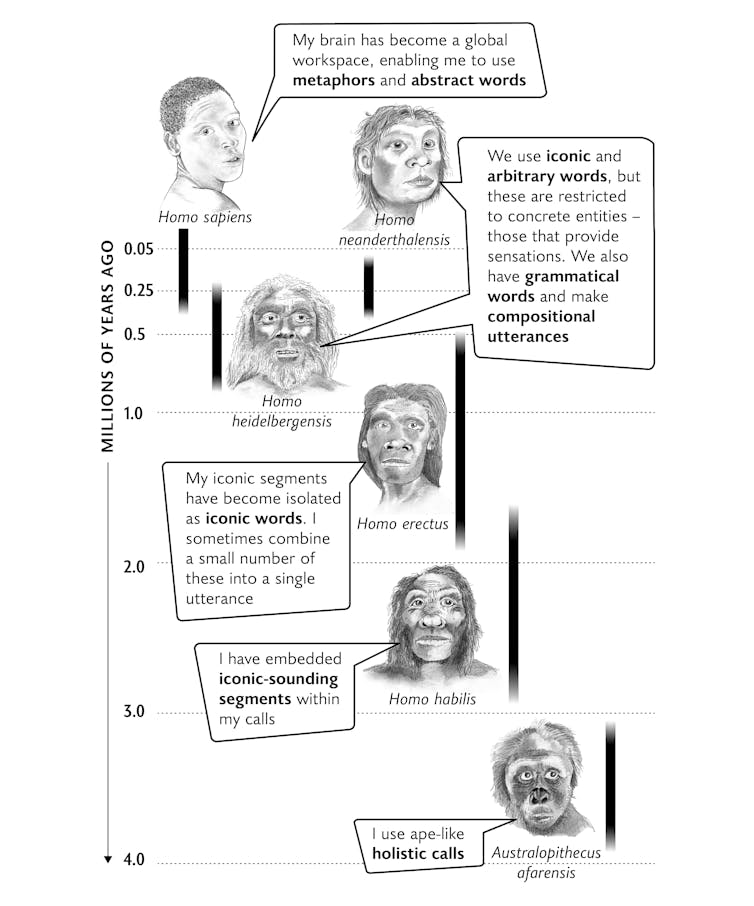

Second is the realization that iconic sounds – those that convey a sensory impression of the thing they represent – have provided the evolutionary bridge between the ape-like calls of our common ancestor 6 million years ago and the first words of Homo – even though we i not sure what kind it was.

Iconic words remain ubiquitous in today’s languages, capturing aspects of the sound, size, movement, and texture of the concept the word represents. This is in contrast to words that have only an arbitrary reference to the thing they refer to. For example, a dog can equally be called a dog, a hound, or a dog – none of which conveys a sensory impression of the animal.

Third, computer simulation models of language transmission between generations have shown that syntax—consistent rules for arranging words to generate meaning—can emerge spontaneously. This shift in emphasis from the genetic coding of syntax to spontaneous emergence suggests that both are the case H. sapiens and the language of the Neanderthals contained these rules.

Steven Mithen, Provided by author (no reuse)

The crucial difference

Although it may be possible to fit the puzzle pieces together in different ways, in my long wrestling with the multidisciplinary evidence I have found only one solution. This begins with iconic words spoken by the ancient human species Homo erectus about 1.6 million years ago.

As these types of words were passed down from generation to generation, arbitrary words and syntax rules emerged that were available to early Neanderthals and… H. sapiens with equivalent linguistic and cognitive skills.

However, these diverged as both species evolved. The H. sapiens The brain evolved its spherical shape with neural networks that connected isolated semantic word clusters. These remained isolated in the Neanderthal brain. So, while H. sapiens While Neanderthals and Neanderthals had the same capacity for iconic words and syntax, they appear to differ in how they stored ideas in semantic clusters in the brain.

By linking together different clusters in the brain responsible for storing groups of concepts, our species gained the ability to think and communicate using metaphors. This allowed modern man to draw a line between very different concepts and ideas.

This was arguably the most important of our cognitive tools, allowing us to develop complex and abstract concepts. While iconic words and syntax were shared between them H. sapiens and Neanderthals, metaphor changed the language, thought and culture of our species and created a deep divide with the Neanderthals. They died out while we populated the world and continue to thrive.