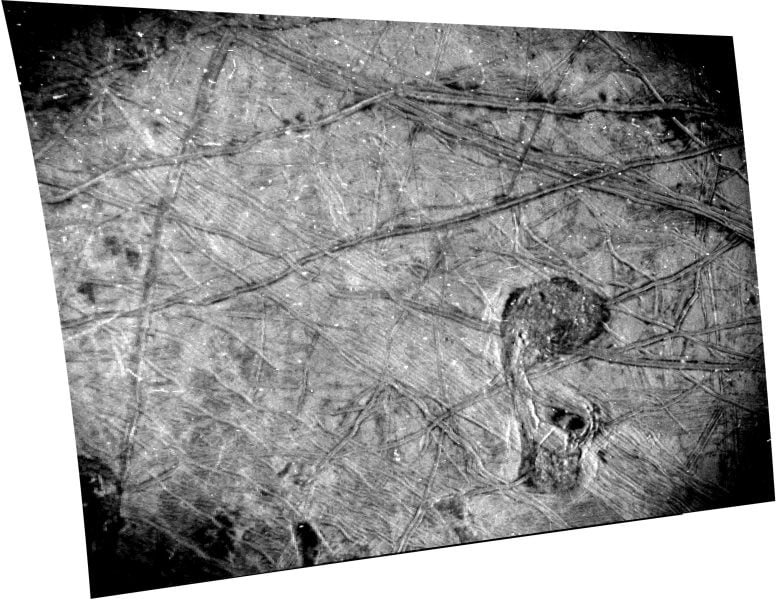

Jupiter’s moon Europa was captured by the JunoCam instrument aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft during the mission’s close flyby on September 29, 2022. The images show the fractures, ridges and bands that crisscross the moon’s surface. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI /MSSS, Björn Jónsson (CC BY 3.0)

NASAJuno has provided images that support the theory of real polar wander on Europa, showing that the moon’s icy shell has shifted. Images from the solar-powered spacecraft revealed intriguing features on Jupiter’s ice-covered moon, including geological disturbances and possible plume activity, suggesting liquid water and brine are reaching the surface.

Images captured by the JunoCam visible light camera aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft support the theory that the ice crust at the north and south poles of JupiterThe moon Europa is no longer where it once was. Additionally, a high-resolution image from the spacecraft’s Stellar Reference Unit (SRU) shows evidence of possible plume activity and disturbances in the ice shell, suggesting that brine may have recently bubbled to the surface.

The JunoCam results were recently published in the Planetary Science Journal and the SRU results were published in the journal JGR planets.

On September 29, 2022, Juno made its next flyby of Europa, coming within 220 miles (355 kilometers) of the Moon’s frozen surface. The four images taken by JunoCam and one by the SRU are the first high-resolution images of Europe since Galileo’s last flyby in 2000.

True polar migration

Juno’s ground orbit over Europa enabled images to be taken near the lunar equator. When analyzing the data, the JunoCam team found that in addition to the expected ice blocks, walls, scarps, ridges and valleys, the camera also captured irregularly distributed, steep-walled depressions 20 to 50 kilometers wide. They resemble large egg-shaped pits previously found in images from other locations in Europe.

A vast ocean is thought to lie beneath Europa’s icy exterior, and these surface features have been linked to “true polar wander,” a theory that suggests Europa’s outer icy shell is essentially free-floating and moving.

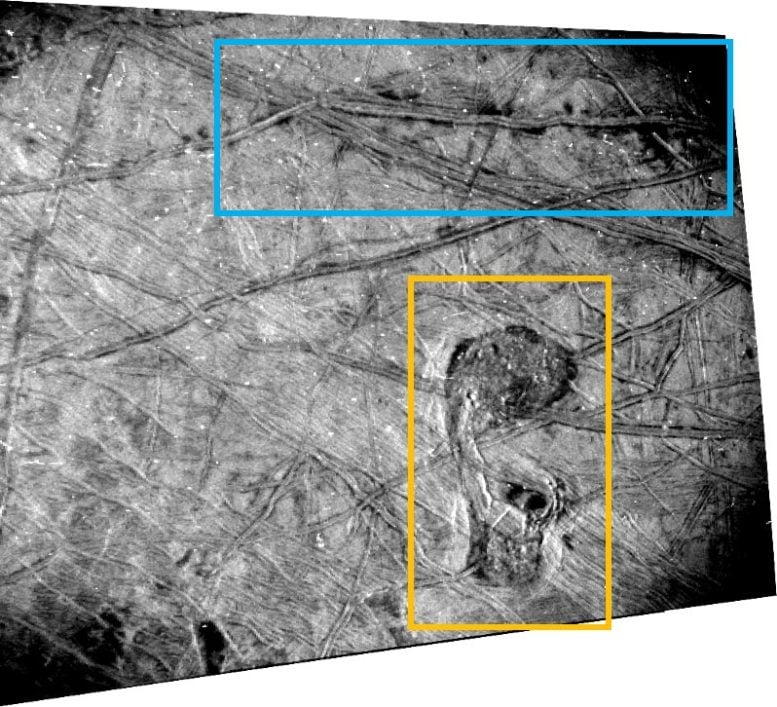

This black-and-white image of Europa’s surface was captured by the Stellar Reference Unit (SRU) aboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft during its flyby on September 29, 2022. The chaos feature nicknamed “the platypus” can be seen in the bottom right corner. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI

“True polar wander occurs when Europa’s icy shell becomes decoupled from its rocky interior, causing high stresses on the shell that lead to predictable fracture patterns,” said Candy Hansen, a Juno co-investigator who is leading the planning for JunoCam at the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona. “This is the first time that these fracture patterns have been mapped in the Southern Hemisphere, suggesting that the impact of true polar wander on the surface geology of Europe is more extensive than previously thought.”

The high-resolution JunoCam images were also used to reclassify a previously prominent surface feature from the map of Europe.

“Crater Gwern no longer exists,” Hansen said. “What was once thought to be a 13-mile-wide impact crater – one of Europe’s few documented impact craters – Gwern, was revealed in JunoCam data to be a series of intersecting ridges that created an oval shadow.”

This annotated image of Europa’s surface from Juno’s SRU shows the location of a double ridge running east-west (blue box) with possible plume patches and the chaos structure the team calls “the platypus” (orange box). These features indicate current surface activity and the presence of subsurface liquid water on Jupiter’s icy moon. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI

The platypus

Although all five of Juno’s Europa images are high-resolution, the image from the spacecraft’s black-and-white SRU provides the most detail. The SRU is designed to detect faint stars for navigation purposes and is sensitive to dim light. To avoid over-illuminating the image, the team used the camera to photograph the nightside of Europa while it was illuminated only by sunlight scattered from Jupiter (a phenomenon called the “Jupiter glow”).

This innovative imaging approach made it possible to highlight complex surface features and reveal intricate networks of intersecting ridges and dark spots of potential water vapor plumes. A fascinating feature that covers an area of 23 miles by 42 miles (37 kilometers by 67 kilometers) was nicknamed “the platypus” by the team because of its shape.

Characterized by chaotic terrain with hills, prominent ridges and dark reddish-brown material, the platypus is the youngest feature in its neighborhood. Its northern “hull” and southern “beak”—connected by a fractured “neck” formation—disrupt the surrounding terrain with a lumpy matrix material containing numerous ice blocks ranging from 0.6 to 4.3 miles (1 to 7 km) wide kilometers). At the edges of the platypus, ridge formations collapse into the structure.

For the Juno team, these formations support the idea that Europa’s ice shell could be giving way in places where there are pockets of salt water from the subsurface ocean beneath the surface.

About 50 kilometers north of the platypus is a series of double ridges flanked by dark patches similar to features found elsewhere on Europa, which scientists say are cryovolcanic cloud deposits.

“These features suggest present-day surface activity and the presence of liquid water beneath Europa’s surface,” said Heidi Becker, lead co-investigator for the SRU at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which also leads the mission. “The SRU image is a high-quality baseline for specific locations on NASA and ESA’s Europa Clipper mission (European Space Agency‘s) Juice missions may aim to look for signs of change and salt.”

Europa Clipper’s focus is on Europa – including studying whether the icy moon might have suitable conditions for life. Launch is scheduled for autumn 2024 and arrival at Jupiter in 2030. Juice (Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer) launched on April 14, 2023. The ESA mission will reach Jupiter in July 2031 to explore many targets (the three large icy moons of the Jupiter) as well as fiery Io and smaller moons as well as the atmosphere, magnetosphere and rings of the planet) with a special focus on Ganymede.

Juno conducted its 61st close flyby of the gas giant on May 12. Its 62nd flyby of the gas giant, scheduled for June 13, will include an Io flyby at an altitude of about 18,200 miles (29,300 kilometers).

References:

“Juno’s JunoCam Images of Europa” by CJ Hansen, MA Ravine, PM Schenk, GC Collins, EJ Leonard, CB Phillips, MA Caplinger, F. Tosi, SJ Bolton and Björn Jónsson, March 21, 2024, The Planetary Science Journal.

DOI: 10.3847/PSJ/ad24f4

Reference: “A Complex Region of Europa’s Surface with Evidence of Recent Activity Revealed by Juno’s Stellar Reference Unit” by Heidi N. Becker, Jonathan I. Lunine, Paul M. Schenk, Meghan M. Florence, Martin J. Brennan, Candice J. Hansen, Yasmina M. Martos, Scott J. Bolton and James W. Alexander, December 22, 2023, Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

DOI: 10.1029/2023JE008105

JPL, a division of Caltech in Pasadena, California, is managing the Juno mission for principal investigator Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA’s New Frontiers program, managed at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Italian Space Agency (ASI) funded the Jovian InfraRed Auroral Mapper. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built and operates the spacecraft.